Women’s History Month honors and celebrates the struggles and achievements of American women throughout the history of the United States. American women have struggled throughout our history to gain rights not simply for themselves but for many other under represented and disenfranchised groups in America.

As we celebrate and honor women across the U.S. and globe, each week we’ll pay special homage to women who have made important contributions in the areas of medicine and health care.

March 1st-7th

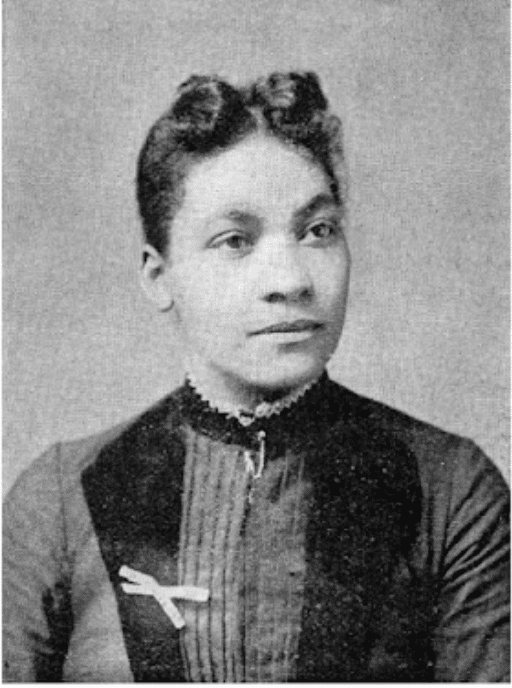

Letitia Mumford Geer

Inventor & Nurse (1852-1935)

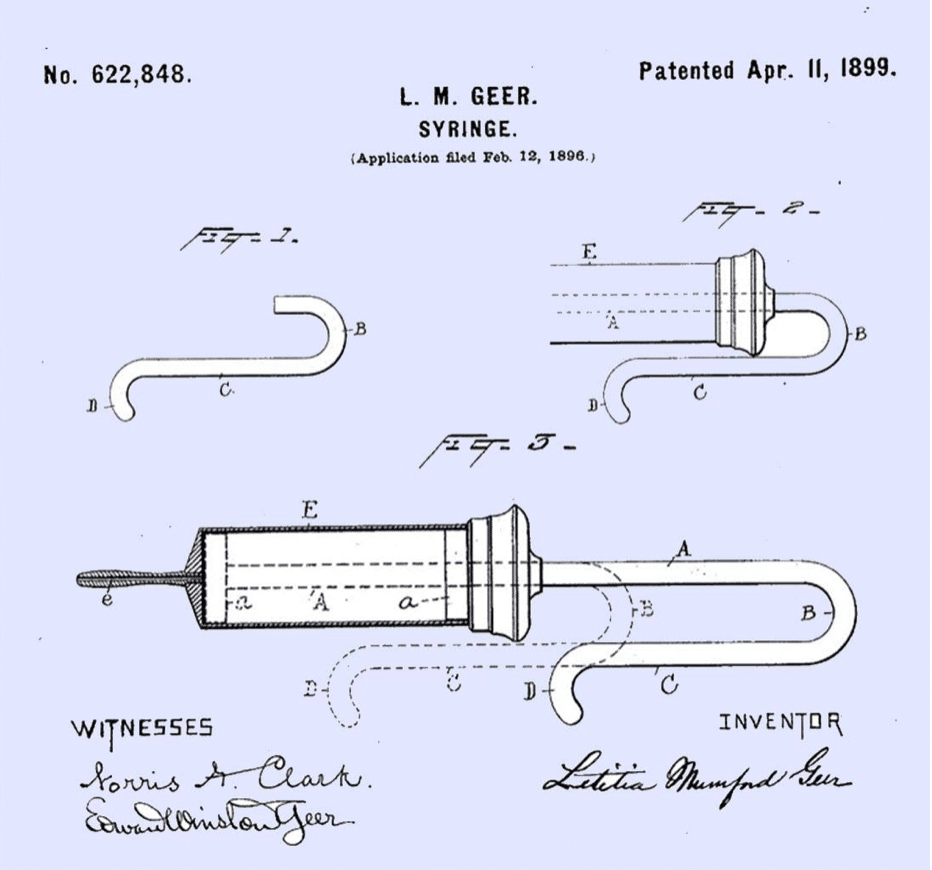

On February 12, 1896 Letitia Mumford Geer, a native New Yorker, filed for a patent for a new design for the medical syringe. The patent for the one-handed syringe design was granted in 1899. Her newly-patent design helped revolutionize health care, making it easier for health care workers and for patients.

Her syringe design includes a cylinder, piston rod, a handle and nozzle. The piston rod had a U-shaped handle for easier grip. The handle was designed in a way to be reached even in extreme positions. The hook at the free end of the syringe prevented hands from slipping.

Geer’s design of the medical syringe had many unique advantages.  The syringe is very simple and cheap. It can be operated with one hand. The syringe can be used for rectal injections and similar purposes and it can be operated by either the physician or the patient. In fact, today’s modern syringes are inspired from Geer’s original idea.

The syringe is very simple and cheap. It can be operated with one hand. The syringe can be used for rectal injections and similar purposes and it can be operated by either the physician or the patient. In fact, today’s modern syringes are inspired from Geer’s original idea.

Letitia Mumford Geer passed away in 1935 in Kings County New York at the age of 83.

United States Patent and Trademark Office

March 8th-14th

Virginia Apgar, MD

American medical researcher and educator

(1909-1974)

Virginia Apgar, MD, is known best for developing the “Apgar scoring” system, a method used for evaluating newborns viability.

Apgar graduated from Mount Holyoke College in 1929. In 1933, she graduated fourth in her class from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and completed a residency in surgery in 1937.

In 1949, Apgar became the first woman to become a professor at Columbia, where she remained until 1959. In 1953, she introduced the first test, called the Apgar score to assess the health of newborn babies.

Between the 1930s and the 1950s, the U.S. infant mortality rate decreased, but the number of infant deaths within the first 24 hours after birth remained constant. Apgar noticed this trend and began to investigate methods for decreasing the infant mortality rate specifically within the first 24 hours of the infant’s life. As an obstetric anesthesiologist, Apgar was able to document trends that could distinguish healthy infants from infants in trouble.

This investigation led to a standardized scoring system used to assess a newborn’s health after birth, with the result referred to as the newborn’s “Apgar score.” By the 1960s, many hospitals in the U.S. were using the Apgar score consistently. The score continues to be used to provide an accepted and convenient method for reporting the status of the newborn infant immediately after birth.

This investigation led to a standardized scoring system used to assess a newborn’s health after birth, with the result referred to as the newborn’s “Apgar score.” By the 1960s, many hospitals in the U.S. were using the Apgar score consistently. The score continues to be used to provide an accepted and convenient method for reporting the status of the newborn infant immediately after birth.

Apgar published more than sixty scientific articles and numerous shorter essays during her distinguished career, along with her book, Is My Baby All Right?. She received many awards, including honorary doctorates from renowned colleges and universities.

Apgar passed away in 1974 but continues to earn posthumous recognition for her contributions and achievements.

March 15th-21st

Rebecca Lee Crumpler

First African-American woman physician in the United States

(1831-1895)

Rebeca Crumpler was born in Delaware in 1831 and later lived in the Philadelphia region, where she was raised by her aunt who often helped care for sick people in her neighborhood.

Rebecca worked as a nurse before attending the New England Female Medical College in  1864 where she became the first African-American woman graduate. To give further perspective to Dr. Crumpler’s great achievements — in 1860, only 300 of the 54,543 physicians in the U.S. were women.

1864 where she became the first African-American woman graduate. To give further perspective to Dr. Crumpler’s great achievements — in 1860, only 300 of the 54,543 physicians in the U.S. were women.

Following her graduation, Dr. Crumpler briefly practiced In Boston, but at the end of the Civil War found herself drawn to Richmond, Virginia where she worked in association with the Freedman’s Bureau as well as with community and missionary groups. Dr. Crumpler is also known as one of the first African-American authors of a medical publication, “A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts.” The publication features advice on treating illness in infants and young children and women of childbearing age.

Dr. Crumpler passed away on March 9, 1895 in Boston and is buried in Fairview Cemetery in Boston.

Public Broadcasting Service

National Park Service

March 22nd-28th

Ida Hyde

American physiologist

(1857-1945)

Ida Henrietta Hyde, was born in Davenport, Iowa on September 8, 1857. She was one of the  first female physiologists, a champion for women scientists, and the inventor of the microelectrode. Ida grew up in Chicago, where she attended public school and worked as a dressmaker and milliner. By the age of 24 Ida was able to attend one year of college at the University of Illinois and in 1882 became an elementary school teacher. She was instrumental for introducing science curriculum to her students in Chicago public school system.

first female physiologists, a champion for women scientists, and the inventor of the microelectrode. Ida grew up in Chicago, where she attended public school and worked as a dressmaker and milliner. By the age of 24 Ida was able to attend one year of college at the University of Illinois and in 1882 became an elementary school teacher. She was instrumental for introducing science curriculum to her students in Chicago public school system.

By 1889 Ida was able to return to college and attended Cornell University where she earned her bachelor’s degree in biological science in 1891. In 1893 Ida was presented the opportunity to study in Germany on a fellowship to pursue a PhD at Heidelberg University. Despite many hurdles and delays, Ida received her doctorate in 1896. She became the first woman to receive a doctorate in science at Heidelberg, and the third American woman to receive a doctorate in Germany.

In 1898, Dr. Hyde moved to the University of Kansas, where she helped establish the physiology department and served as its first chair, wrote two textbooks on physiology, and invented a novel microelectrode that could both stimulate cells and record their electrical activity. She became a specialist in the physiology of both invertebrates and vertebrates. In 1902, Dr. Hyde became the first woman to be elected to the American Physiological Society. She died in 1945 at age 87.

Physics Today

ISpyPysiologyBlog